On 4 June, India concluded its 18th national parliamentary election. Almost one billion voters were asked to cast their vote in a six-week long election that by most observers was expected to become another win for Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The BJP did not disappoint. On 9 June, Narendra Modi took his oath of office for the third time. Yet, the cards were reshuffled.

A bittersweet victory for the ruling party

With 240 of the 543 seats in the lower house of the Indian parliament (the Lok Sabha), the BJP again emerged as the strongest party. However, its victory is bittersweet. Compared to its 2019 election result, the BJP is down by 63 seats, losing its outright majority in parliament (272 seats). Hence, the BJP had to rely on its partners in the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) to achieve 294 seats and form the government, making coalition politics a reality for the next five years. The outcome comes as sigh of relief for those who saw Indian democracy threatened by the overwhelming BJP political juggernaut, signalling a revival of the federal and pluralistic spirit of Indian politics.

The oppositional Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), led by the Indian National Congress, was able to achieve 232 seats, in spite of a playing field that they argued was anything but level – with media coverage, party funding, and state institutions and resources cornered by the ruling BJP. Even though the NDA was quick to form the new government, the coalition calculators are likely to remain out as power negotiations will be protracted, with the smaller non-aligned parties and independents (17 seats) potentially becoming king-makers in coalition set-ups. The necessity of coalition politics, which the BJP was able to conveniently do without over the last two terms, will test the adaptability of its leadership.

Even though the prime minister remains a hugely popular politician by international standards, his image as an invincible leader is tarnished. This, together with the fact that he is unlikely to run for a fourth term, opens up a new era for the ruling party, likely characterised by heightened power tussles within its ranks.

Tumultuous election phase challenges BJP

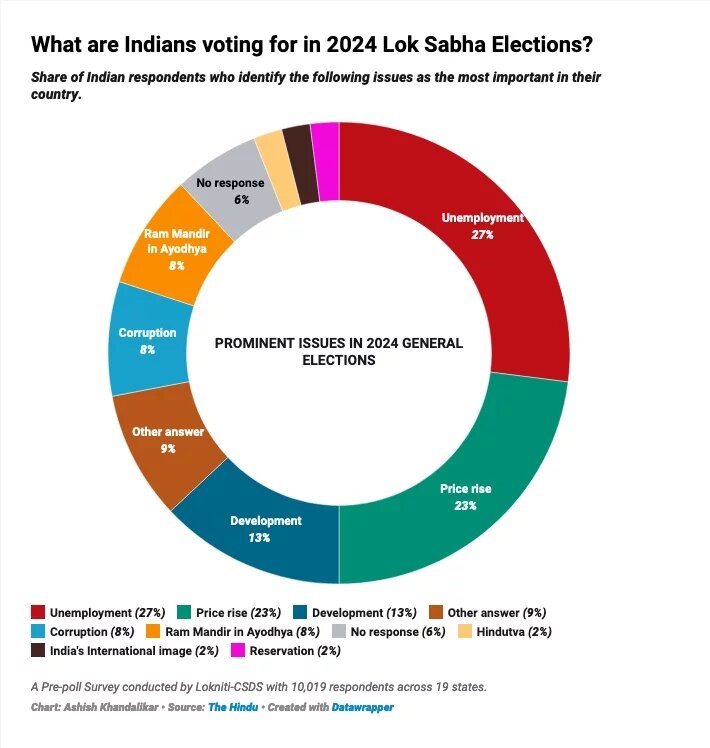

The ruling BJP entered the election with the proven formula of centring its campaign on Modi as a person, Hindu nationalism and the portrayal of India as a country destined for a greater future. The INDIA alliance, led by the Congress, on the other hand, sought to position the election as a vote on India’s democratic future, and emphasized issues of justice and redistribution in an increasingly unequal society. The electioneering between the two major contenders hit fever pitch when Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed that if elected to power, the Congress would distribute people’s property among Muslims. Beyond such political theatrics, a pre-poll survey by Lokniti-CSDS, a public opinion research initiative, revealed what Indians are actually most concerned about: unemployment, inflation and development.

Despite regularly emphasizing its confidence to increase the NDA’s share in the Lok Sabha to more than 400 seats, the BJP midway into the election appeared unsettled by the fact that its usual approaches did not seem to catch on as expected among the electorate, doubling down on hateful rhetoric against Muslims and attacks on the opposition. Amidst the slander from all sides, the Electoral Commission was seemingly unwilling to act as the clear authority over the election process and reign culprits in.

The final election result is difficult to read in a uniform way, but the mass appeal of aggressive Hindu nationalism seems to have its limits, and negative sentiment about economic realities in the everyday lives of people, especially in small-town India, prevailed over the heady national growth rate figures of more than seven per cent touted by the BJP as proof for their success.

The BJP lost in the key battleground states of Uttar Pradesh, a heartland of Hindu national politics, and Maharashtra, one of India’s largest states, and was unable to make significant gains in opposition strongholds such as the southern state of Tamil Nadu. In northeastern Manipur, the opposition won both seats in the context of a prime minister silent on a violent conflict that erupted in May 2023, and which has been smouldering since. Perhaps the most symbolic loss for the BJP, however, was that of the seat in Faizabad, the constituency where the Ram Temple of Ayodhya (considered birthplace of Lord Ram) was consecrated with great fanfare in January by Prime Minister Modi in an attempt to boost Hindu pride and thereby the BJP’s election prospects.

An anti-incumbency sentiment could be seen for both the NDA and the INDIA alliance, with each faltering in as many as six key states where they are currently in power.

Democratic relief and the BJP’s political tightrope

Liberal media and civil society are rejoicing at the election results, as they interpret the outcome also as vote against the increasingly authoritarian streak the BJP showed over the past term. In recent years, several critical media houses have been clamped down on and numerous civil society organisation have lost their license to receive funds from abroad, effectively shutting them down. This development has been mirrored in India’s increasingly poor performance in several international rankings on democratic indicators. The prospect of a brute majority for the BJP for a third term was largely seen by the sector as the potential death knell for an open civic space in India.

Prime Minister Modi, for his part, has already announced that big decisions will be made in his third term. According to him, the thrust of his new government will be to end corruption. However, the perceived closeness of the BJP to India’s large conglomerates, whose value have sky-rocketed in recent years while making huge donations to the party, make critical observers cast doubt on the depth of such commitments; with the other question being how NDA coalition partners will be reined in on this critical issue.

In order to strengthen economic growth and deepen its impact on employment, Modi is also said to be planning business-friendly reforms that ought to make foreign investment more attractive and boost India’s share in global manufacturing. Despite India’s massive infrastructure investments in recent years, increased private investment will be necessary to sustain growth. Whatever reforms the new BJP-led government decides to pursue, it will have to tread with more caution with regard to the sentiment in the country, and consider the views and interests of its coalition partners.

Although there is again no Muslim among the newly appointed cabinet members, the leaders of the two largest coalition partners have already made it clear that they will not stand for politics of communal polarisation, protecting their Muslim support base.

At the same time, they have already made clear demands on the central government they are now part of: special economic packages for their home states of northern Indian Bihar and southern Indian Andhra Pradesh, respectively.

In addition, the farmers movement, that in the wake of its large protests in February has contributed to the BJP’s significant losses in some northern states, is likely to step up attacks on the government concerning any move that is seen as an unbalanced allocation of development packages, subsidies and other perks. There are also state elections coming up in several important states, including Bihar and Maharashtra.

How well the BJP can balance the political tightrope and manage the centrifugal forces in its own government remains to be seen. To likely satisfy everyone’s interests, the latest Modi government has begun with the largest Council of Ministers to date, leaving minimal room for future expansion.

Likely continuity in foreign policy

The BJP’s return to power, even within a coalition government, suggests overall continuity rather than change in its foreign policy and national security agenda. The new government, with Subrahmanyam Jaishankar again as Minister of External Affairs, is likely to remain steadfast in its commitment to the core approach that has characterized foreign policy over the last decade: an assertive and muscular stance embedded in the country’s civilizational identity.

Noteworthy is how the BJP popularised foreign policy within the electoral discourse, traditionally a domain with limited domestic sway. The campaign prominently included topics such as India’s political rise on the world stage under Modi. While Modi himself has often articulated India’s role as that of a ‘Vishwaguru’ (teacher of the world), the BJP manifesto notably made a shift of tone and transitioned the self-centred language to ‘Vishwabandhu’ (friend of the world). But India’s ‘Bharat First’ foreign policy that, at the global level, emphasizes multipolarity and strategic autonomy is likely to remain. India’s continued close partnership with Russia while steadily strengthening ties with the West aligns with this stance. As India continues to be threatened by China’s aggressive diplomatic, military and strategic manoeuvres across its Himalayan borders, West Asia and the Indian Ocean, the closeness to the West is bound to remain part of this shared concern.

However, while Europe navigates its fractious relations with China, it considers Russia its main adversary against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine. In contrast, India perceives China as its primary threat while maintaining significant ties with Russia. This makes for a conflictual outlook, but both regions are also motivated to mitigate security risks and leverage their strengths in areas like maritime security, infrastructure and technology to maintain stability and protect their interests across Eurasia.

In a move that signals a re-emphasis on India’s ‘neighbourhood first’ policy and countering Chinese influence in the region, New Delhi invited the heads of state of Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles and Sri Lanka to the swearing in of the new government.

Steady progress but uncertainty in EU relations

The election outcome is unlikely to change the fundamentals of India–EU relations that have progressed in recent years. However, the relationship continues to be also defined by unfulfilled potential and promises. The most recent setback is the cancellation of the bilateral summit, necessitating a reassessment of the ‘EU-India Strategic Partnership: A Roadmap to 2025’. Despite challenges, trade presents opportunities. The recently concluded trade deal with the European Free Trade Association, as well as the EU surpassing the US as India’s largest trading partner, point to the potential for concluding the drawn out EU-India Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations. Given the EU’s historically low investment in India, creating a conducive business environment will be crucial.

As the political pendulum has swung back towards the middle in India – to the relief of European decision makers, who, albeit largely silently, were concerned about the health of Indian democracy – the EU election results represent a rightward populist drift in Europe, throwing up uncertainties for the future of the EU’s approach to foreign affairs. Should ultra-nationalist sentiments gain substantive traction, there is a risk of losing the momentum in EU–India relations. This could be particularly true for trade negotiations as European right-wing governments have proven to be rather critical of making large trade deals. At the same time, Europe’s interest in reducing India’s Russia dependency in the defence sector, given the war in Ukraine, is likely to remain.